Autoimmune disease overview

Autoimmune diseases are a group of conditions where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue. Typically, the immune system protects your body from harmful invaders like viruses and bacteria. In autoimmune diseases, the immune system gets confused and starts attacking parts of the body like the pancreas or joints as if they were dangerous germs. Scientists, including many at BRI, are working to understand exactly how and why this happens.

There are over 100 different types of autoimmune diseases that affect different parts of the body, including:

- Skin (psoriasis, scleroderma)

- Joints (rheumatoid arthritis)

- Nervous system (multiple sclerosis)

- Gut (ulcerative colitis)

- Endocrine system (Type 1 diabetes and thyroid disease)

People with different autoimmune diseases experience very different symptoms, from joint pain, to digestive problems, to skin rashes. People with the same disease may even experience different symptoms or different severity of disease.

What Are the Most Common Autoimmune Diseases?

Some of the most common autoimmune diseases include:

- Type 1 diabetes

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- Multiple sclerosis (MS)

- Lupus

- Psoriasis

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- Addison’s disease

- Graves’ disease

1 in 22

110+

4:1

Do Genetics Play a Role in Autoimmune Diseases?

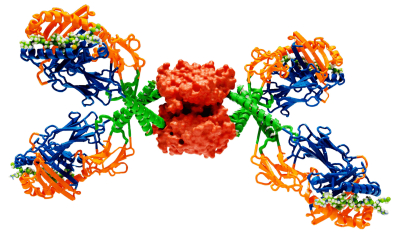

Genetics play a key role in autoimmune diseases. BRI scientists have been a leading force in identifying specific genes that make a person more likely to develop autoimmune diseases. Certain genes are also connected to more than one autoimmune disease. For example, a gene called HLA-DRB1 plays a role in T1D, RA, MS and lupus.

In general, people who have a close family member with autoimmune disease — like a parent, sibling or child — are more likely to develop an autoimmune disease. Sometimes one disease, like T1D, runs in families. Other times autoimmune diseases in general run in families; one sibling may have RA while another develops T1D.

Having a close family member with an autoimmune disease does not mean you will develop one. It just means your risk is a little higher than that of the general population.

Genetics research in autoimmune disease

BRI scientists aren’t only studying genes — we’re studying other genetic material as well. Interestingly, only about 1% of your genetic material is genes. What about the other 99%? Scientists are still working to find out. BRI’s team is conducting research to learn more about this genetic material and if and how it affects autoimmune diseases.

Our team is also conducting research into why people with Down syndrome are much more likely to develop autoimmune diseases than people without Down syndrome. Down syndrome happens when a person has a full or partial extra chromosome (chromosomes are tiny structures where genes and genetic material are stored). This research aims to inform better autoimmune disease care for people with Down syndrome and learn whether the extra genetic material associated with Down syndrome could provide more insight into the connection between genetics and autoimmune disease.

Support Autoimmune Disease Research at BRI

Joining one of BRI's biorepositories allows us to make new insights and faster progress in finding ways to predict, prevent and treat human autoimmune disease.

How Do Autoimmune Diseases Start? What Can Trigger Autoimmune Diseases?

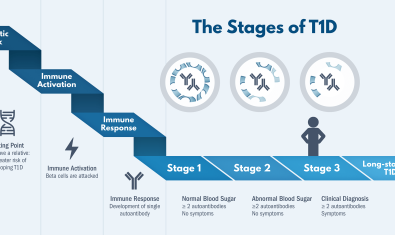

BRI scientists are working to learn exactly how autoimmune diseases start and what might trigger them. This includes investigating whether viruses, bacteria or environmental and lifestyle factors may start the chain reaction that leads to autoimmune diseases, especially in people that have the genes associated with certain diseases.

Autoimmune Diseases in the Pacific Northwest

Autoimmune diseases including MS, IBD and T1D are more common in the Pacific Northwest.

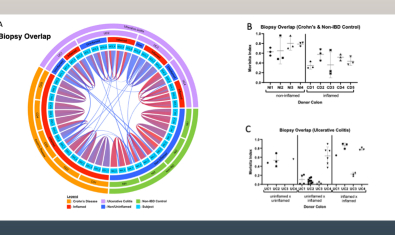

IBD affects approximately 1.4 million people in America (almost one in 200), evenly divided between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. IBD is more common in northern latitudes, like the Pacific Northwest, where an estimated 50,000 people are thought to live with IBD.

MS affects approximately 400,000 people in America, about one in 1,000. It is much more common in the Northwest where it affects approximately 12,000 people two in 1,000.

Scientists are still working to understand why these diseases are more common in the Pacific Northwest. Some possible explanations may be the Northern European/Scandinavian heritage of many people in this region, and other environmental factors.

What Is the Latest Research On Autoimmune Disease?

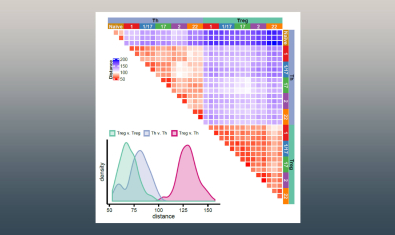

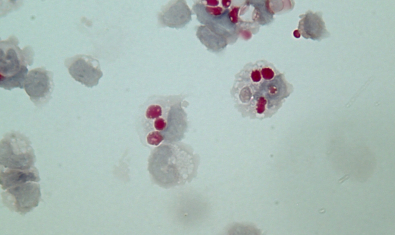

- Creating a map of the immune system. We are studying the underlying cells and processes that lead to autoimmune diseases in precise detail. This will better enable us to predict who will develop autoimmune diseases and provide targets for new treatments.

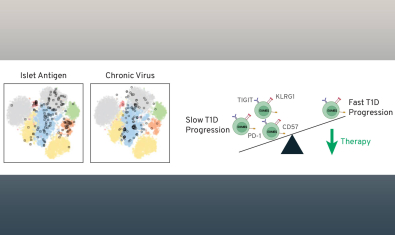

- Preventing autoimmune diseases. One of our key goals is to identify who is on track to develop autoimmune diseases and find therapies to stop the disease before it starts.

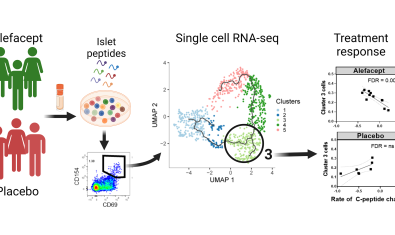

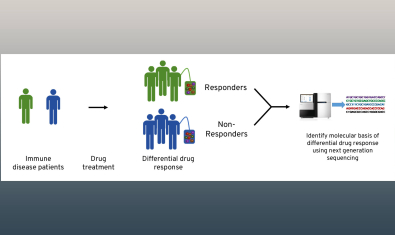

- Informing personalized medicine. Autoimmune disease therapies work differently in different people. One therapy for rheumatoid arthritis might limit joint pain and help a person feel significantly better — while the same therapy might make a different person’s RA worse. We’re working to understand why people respond differently to different therapies and move toward a future where everyone gets the treatment that will work best for them, right away.

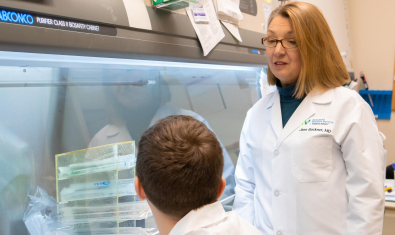

Labs at BRI with an emphasis on autoimmunity

Bettelli Lab

The main focus of the Bettelli Lab is to identify the cell types of the immune system and mechanisms, which induce and regulate the development of autoimmunity.

Buckner Lab

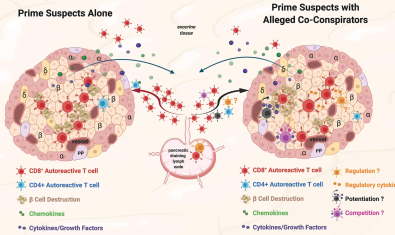

The Buckner Lab is focused on identifying the underlying mechanisms by which regulation of the adaptive immune response fails or is overcome in the setting of human autoimmunity.

Campbell Lab

The Campbell laboratory is interested in understanding the basis for T cell activation, function and tolerance.

Cerosaletti Lab

Dr. Cerosaletti’s research is focused on the role of the adaptive immune system in the development and progression of immune mediated diseases and the response to treatment.

Greenbaum Lab

Our group focuses on prediction and prevention of type 1 diabetes (T1D) as well as discovery and validation of biomarkers of disease progression and response to therapy.

Hamerman Lab

The lab is interested in understanding how myeloid cells contribute to both productive and pathological immune responses during infection, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases.

Harrison Lab

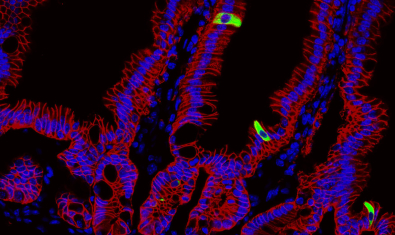

The Harrison Lab studies the mechanisms controlling host-microbe interactions at barrier tissues, primarily the skin and the gut with the goal to understand how these immune cells promote barrier tissue integrity and repair, and to understand how this goes awry during disease.

James Lab

The James lab is working to develop an increasingly in depth knowledge of autoreactive T cell responses by examining the characteristics of the epitope specific cells involved in autoimmune diseases through robust multi-parameter assays and also at the single cell level.

Kwok Lab

The Kwok lab uses tetramers and other antigen specific T cell assays to examine autoreactive T cells in autoimmune diseases in order to provide insights into disease mechanisms and identify strategies for disease intervention.

Linsley Lab

Our goal is to develop and use cutting edge systems biology approaches to elucidate molecular signatures of complex immune diseases, understand the mechanisms of disease, and identify the right therapy for the right patient.

Long Lab

The Long Lab focuses on understanding mechanisms of tolerance, why they are lost in autoimmunity, and how tolerance can be augmented with therapy.

Lord Lab

The Lord lab is investigating how loss of “tolerance” happens in IBD, to learn how the immune system normally coexists peacefully in close proximity to gut contents.

Mikacenic Lab

The Mikacenic lab is focused on understanding how lung immune cells contribute to inflammation, repair, and fibrosis.

Morawski Lab

The Morawski lab studies the adaptive immune response occurring during human inflammatory and autoimmune diseases of the skin and other barrier tissues.

Speake Lab

The Speake group is interested in advancing clinical research – especially in type 1 diabetes, but also in the context of other immune-mediated diseases.

Ziegler Lab

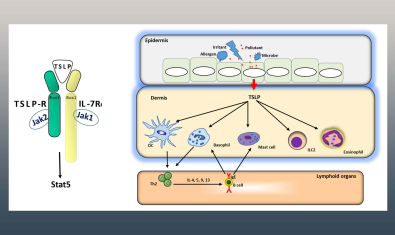

The Ziegler laboratory is investigating the role of the epithelial cytokines TSLP and IL-33 in regulating protective responses at mucosal barrier surfaces such as the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.