11 Things to Know About mRNA Vaccines for COVID-19

In the race for a COVID-19 vaccine, messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines finished first. This includes those made by Pfizer and Moderna. These vaccines use a new approach to fight off pathogens (germs like viruses and bacteria).

We recently talked to BRI’s Adam Lacy-Hulbert, PhD — who has long studied viruses and ways to combat them — to learn more about this new vaccination approach. He shared 11 key things to know about mRNA vaccines.

1. mRNA vaccines are made from a small, harmless piece of the virus’s genetic material

Traditionally, vaccines are made from a very weak form of bacteria or a dead version of a virus. Introducing a weak or dead version of a germ teaches your immune system how to fight it off.

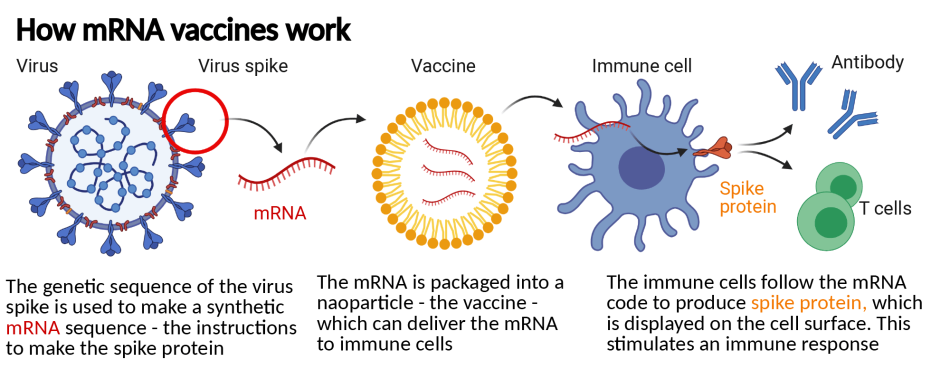

This new type of vaccine starts with a different ingredient: mRNA. All living things have mRNA. Its job is to go to a cell’s command center (the nucleus) and copy the recipe for making certain proteins. Then, it carries that recipe to a cell’s ribosomes. Ribosomes read the recipe and make proteins, which do things like make tissue and fight off invaders in your body.

mRNA vaccines take the recipe for a key protein in COVID-19 and use it to teach your immune system what that protein looks like. This enables your immune system to train new troops to attack that protein. Those troops (antibodies) stick around in your immune system. If you ever encounter COVID-19, they will attack the proteins it's made of, so you don’t get sick.

2. Using a proven approach, this is a new way of making vaccines

While the COVID-19 vaccines are the first mRNA vaccines, this approach has been studied for decades. Scientists were particularly interested in using this approach to alert the body of proteins that were common in cancer cells. This was part of a larger area of research exploring the possibility of an anti-cancer vaccine.

Researchers started investigating the use of an mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 in January 2020 — shortly after the virus was detected but before it spread around the world.

“Research groups had been developing this for years, but no one had got anything to market,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says. “The platform was poised and ready. COVID created the need to deploy it.”

3. Other coronaviruses gave scientists clues about the right piece of genetic code

COVID-19 is a brand-new virus. But it's part of the coronavirus family (which includes SARS and MERS) that has been around for thousands of years.

“When you sequence the genome of different coronaviruses, you can see they all have a common structure made of certain proteins,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says.

Those proteins are key building blocks for the virus. So, if your immune system recognizes and attacks the ingredients the virus is made of, it can fight it off.

“Researchers had a good idea about which part of the protein was important and quickly tested it to make sure,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says. “That allowed them to know which mRNA segment to use rather quickly."

4. The first dose teaches your body to fight off the virus

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines require two doses, about a month apart. Each dose has a purpose. The first one introduces your immune system to the proteins COVID-19 is made of. This triggers an immune response and creates antibodies to fight the virus. But if your body only sees that protein once, the antibodies may disappear over time because your body doesn’t think that invader is a threat anymore.

5. The second dose cements how to fight the virus in your immune system’s memory

The second dose helps your body produce more antibodies and leads your body to remember what that pathogen looks like.

“The immune system responds better when it sees something multiple times,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says. “That induces ‘immune memory.’ This means your body can very quickly remobilize cells to fight off a pathogen, even if it's 40, 50 or 60 years after you had the vaccine.”

6. Teamwork around the world helped get these vaccines to market – fast

Before COVID-19, the fastest vaccine ever made was the mumps vaccine in the 1960s. That took about four years. Most vaccines have taken around ten years to produce. But countless scientists (including many at BRI) pivoted from their typical work to help solve the mysteries of COVID-19.

Researchers did not skip any steps in the scientific process. But having many minds working together, focused on the same questions led to faster answers. In contrast, the mumps vaccine effort was largely led by one scientist.

“These vaccines are a testament to a lot of hard work and to everyone working together — from scientists working out what the virus is made of and the right immune response, to regulators working overtime, and volunteers stepping up to participate in trials,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says.

7. No corners were cut to ensure the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. But the prevalence of COVID-19 helped obtain faster study results.

To know if a vaccine works, scientists collect data about who among study participants gets the virus, and who doesn’t. With a pandemic, a virus is widespread. That means people are more likely to come into contact with the virus — and data about whether or not the vaccine works becomes available faster.

“If a disease is relatively rare, you could end up waiting years to get enough data to know if the vaccine works because people don’t come into contact with that pathogen very often,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says. “In a pandemic, the disease is widespread and people come into contact with it every day. The trial is still rigorous and has to meet all of the same marks, but you can collect data faster because the virus is out there and so prevalent.”

8. Manufacturing and production sped up the process

Given the urgency of the pandemic, these vaccines were tested and manufactured at the same time. The goal was to have large quantities available if and when they got FDA approval for emergency use. If the vaccine had not been approved, the product would have been destroyed.

9. They were the first COVID-19 vaccines, but they won’t be the only ones

In the U.S., two mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 were approved by the FDA for emergency use at the end of 2020. Vaccines that use other approaches will also become available.

“All of the classic approaches are being used and those vaccines are coming online as well,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says. “The mRNA approach has been amazing, but there are lots of vaccines still in development. To get the whole world vaccinated, we’ll need all of them.”

10. mRNA vaccines can be easily adapted to fight other viruses

Now, the infrastructure needed to create mRNA vaccines is in place. We have ways to make them and factories to manufacture them. This puts scientists one step ahead when a new virus emerges.

“Dare I say when the next pandemic hits, in theory, it's very easy to turn this platform against it,” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says. “Of course, you have to do all of the testing to make sure it works, but the process will be exactly the same. It's an amazing system because it's completely tunable to different pathogens.”

11. mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer and autoimmune disease

BRI scientists are always looking for new ways to speed up or slow down the immune system to fight disease. mRNA vaccines could be a new tool to do that.

“Instead of activating the immune system to fight off a virus, could we deactivate the immune system to fight autoimmune disease?” Dr. Lacy-Hulbert says. “If we could establish that, there's a real power of being able to rapidly change it to fight different diseases. All of that power of the mRNA platform could be brought to bear on autoimmune disease — and that's really exciting.”

Immuno-what? Hear the latest from BRI

Keep up to date on our latest research, new clinical trials and exciting publications.