Immunowhat? Making Sense of What It Means to be Immunocompromised

Words like “immunocompromised” are broad by design: They’re meant to encompass how a wide variety of conditions impact the immune system. But when we see headlines like “COVID-19 vaccines might not work as well for people who are immunocompromised” it’s hard to know exactly what that means and if it applies to you.

We recently spoke with BRI immunologist Bernard Khor, MD, PhD. He provided context and clarity for people with immune-related conditions and their loved ones.

What does immunocompromised mean?

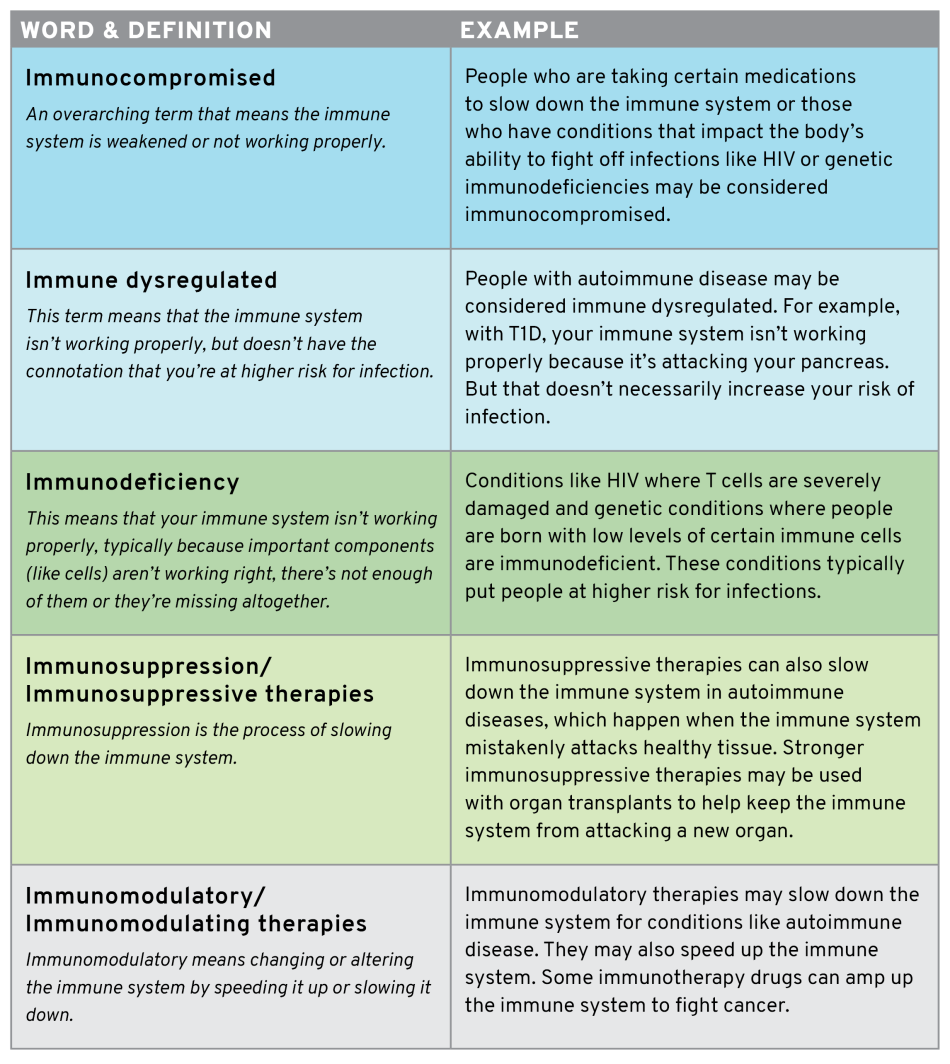

Immunocompromised broadly means that your immune system isn’t working properly, typically in terms of its ability to fight off infection. This could happen for a number of reasons. As people age, their immune system gets weaker, affecting their ability to fight off infections. Immunodeficiencies and medications to suppress the immune system (often called immunomodulatory) can also compromise the immune system.

What is immunodeficient/immunodeficiency?

Immunodeficiency means that your immune system isn’t working properly, typically because important components (like cells) either aren’t present in adequate numbers or aren’t working properly. This can leave a person’s immune system in a weakened state, where it’s not as effective at fighting off bacteria or viruses.

“One well-understood example is people with AIDS (caused by uncontrolled HIV infection),” Dr. Khor says. “You see immune problems caused by the absence of important cells like T cells. There’s a physical deficiency that you can measure.”

What does immunomodulatory mean?

Immunomodulatory means changing or altering the immune system. Immunomodulatory therapies may slow down the immune system for conditions like autoimmune disease (which happens when the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue). They may also speed up the immune system. For example, immunotherapy drugs can amp up the immune system to fight cancer.

What is immunosuppressed/immunosuppression?

Immunosuppression is the process of slowing down the immune system. Immunosuppressive therapies may be used with organ transplants to help keep the immune system from attacking a new organ.

Immunosuppression can also treat some autoimmune diseases. These therapies are typically not as strong as those used for organ transplants. With autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and multiple sclerosis, doctors use these therapies to slow down the immune system’s attack.

“But the immune system is like a seesaw, it needs to be in balance for people to stay healthy,” Dr. Khor says. “If you tip it too far in one direction, it can slow the immune system down too much. This could make someone prone to infection or make them not respond as well to a vaccine.”

Scientists are still working to refine these therapies so they can slow down the attack on healthy tissue, but not so much that it impairs the ability to fight infection or respond to vaccines. Dr. Khor used the analogy of a football team, where one player is running too fast.

“The drugs we have often aren’t targeted enough to just reduce that person’s speed,” he says. “Instead, we have to slow down all of the players on that part of the field. And that alters the performance of the entire team.”

Does having autoimmune disease mean you’re immunocompromised? For example, are people with type 1 diabetes immunocompromised?

The term “immunocompromised” typically implies that your immune system is weaker than it should be. People with autoimmune disease aren’t typically considered immunocompromised, unless they take certain medications that slow down their immune system.

“The connotation for immunocompromised is that the immune function is reduced so you are more prone to infection,” Dr. Khor says. “Typical autoimmunity — say someone with type 1 diabetes (T1D) — is not necessarily associated with a highly increased risk of all infections or ineffective vaccine response.”

Dr. Khor explained that “immune dysregulated” could be a better term for most people with autoimmune disease. That means that the immune system isn’t quite working right, but that doesn’t necessarily impact your ability to fight off infection or respond to a vaccine.

I have read that some immunocompromised people may not mount a strong immune response to vaccines. Is this true? What does that mean?

In general, vaccines help train your immune system to fight off diseases. They do this by teaching the immune system to recognize an invader (say COVID-19) and attack if they see it, for example by making tiny proteins called antibodies. A “strong immune response” means the immune system has the right players in place, they know the game plan, and they’re strong enough to beat the other team.

But some people’s immune systems might have trouble training those proteins: Immunosuppressive drugs might slow some players down. With immunodeficiencies like HIV, people may be missing some players altogether.

“If everyone is moving slower or if you’re missing players, that might make it difficult to score a touchdown,” Dr. Khor says. “If the immune system is suppressed or missing certain components, it’s hard for the immune system to create the antibodies to fight off a virus.”

Most people with autoimmune diseases can make a protective response to vaccines. However, some therapies may change the body’s ability to respond to vaccination, including COVID-19 vaccination. BRI scientists are working hard to understand which medications impact the ability to respond to immunization, and how big of an impact this may have on infection risk.

The CDC recommends getting vaccinated as soon as possible and talking to your healthcare provider if you have questions about COVID-19 vaccination and underlying conditions.

For COVID-19, are there other options for people who might not mount a strong response to vaccines?

Scientists are working to create strategies for people who might not produce a strong response to COVID-19 vaccines – like people taking anti-rejection medications after a solid organ transplant or those with some genetic immunodeficiencies. Some approaches include:

Adapting vaccines for certain populations

Scientists are studying populations who have a weaker-than-usual immune response, with the goal of finding ways to improve that response. This includes testing strategies like using higher vaccine doses and other ways to stimulate the immune system so it responds more strongly.

Treatment hiatus

Some people whose immune systems aren’t responding well because of medicine that suppresses the immune system may be able to pause treatment and get the vaccine.

“Doctors may examine the possibility of taking someone off that drug, getting the vaccine and starting the drug again,” Dr. Khor says.

Finding other forms of protection

Scientists are also examining alternative ways to protect against the virus for people who may not mount a strong immune response to the vaccine. For example, a strategy called passive immunization may provide short-term immunity to a disease through transferring antibodies from one person to another, often through blood or plasma transfusion.

“Vaccines are the first line of defense but there are other strategies,” Dr. Khor says. “Scientists are studying ways to give people passively transferred antibodies or additional therapies that could help protect against the virus.”

How can we protect our loved ones who may not be protected by the COVID-19 vaccine?

First, Dr. Khor recommends that the loved ones of immunocompromised people get vaccinated.

“The more people are vaccinated, the fewer places the virus can hide, live, mutate and spread to those who are especially vulnerable,” he says.

People in close contact with high-risk populations can also continue to live in ways that minimize their risk of being exposed to COVID-19. That might mean gathering only with vaccinated or small groups, wearing masks, doing activities outdoors and avoiding crowded indoor spaces. Dr. Khor has continued to take many of these precautions despite being vaccinated, because his wife works in close contact with high-risk groups.

“Part of this challenge is not having all the answers,” he says. “For example, there are still questions about whether vaccinated people can spread the virus and if so, how likely that is. While we’re building better tools, better treatments and developing better understanding, for me there’s a component of personal choice. How much is this thing I want to do worth? Is it worth passing the virus to someone at risk?”

What is BRI doing to advance research surrounding vaccines for people with autoimmune disease and other conditions?

Most people with autoimmune diseases create a protective response to vaccines. BRI researchers are working to answer specific questions surrounding how some medications for these conditions may impact the ability to respond and if so, how much. Dr. Khor is also working on a study looking at how having Down syndrome affects the body’s response to COVID-19 vaccines. All of this work feeds into BRI’s larger goal of better understanding the immune system and working to predict, prevent and reverse disease.

“At BRI, we've developed much more sophisticated tools to bring to bear on this kind of problem,” Dr. Khor says. “For example, with vaccine response, we know the defense isn’t working right in some people. Next, we hope to figure out which particular player isn’t working right, and why. We want to develop a pipeline that allows us to say ‘it’s player number 74, he needs to run 2 miles per hour slower. It's this specific cell and it needs this exact change’ — and to have therapies that allow us to do that.”

Please consult with your health care provider if you have concerns about your health and before making any changes to your treatment plan.

Immuno-what? Hear the latest from BRI

Keep up to date on our latest research, new clinical trials and exciting publications.