How BRI is Fighting Type 1 Diabetes

When Merry Malnar was 11 years old, her mom took her in for a routine physical and asked the doctor to test for type 1 diabetes (T1D). Merry seemed perfectly healthy, but T1D ran in the family and her mom feared Merry would inherit it too.

“That night, they called and said I had type 1 and that I needed to check into the hospital the next morning,” Merry says. “I remember the exact date —July 24, 1986— because my life hasn’t been the same since.”

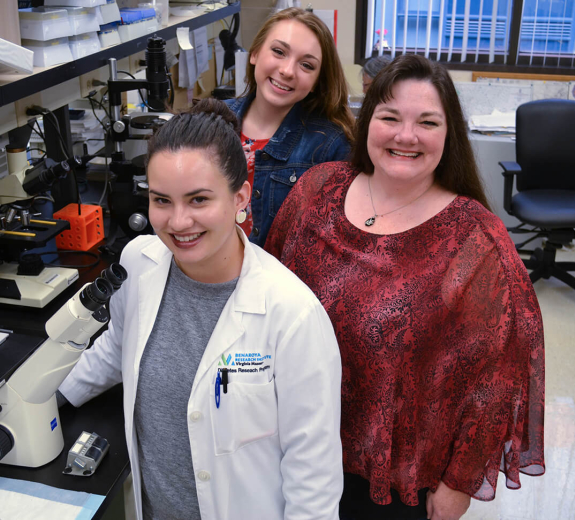

Merry spent a week in the hospital, getting a crash course in controlling her blood sugar. Now she’s guiding her 15-year-old daughter, Kayleigh, through many of the same lessons. Kayleigh has early-stage T1D and, while T1D treatment has improved dramatically in the past 30 years, the disease still comes with a litany of potential consequences, including heart disease and stroke.

That’s why Merry and Kayleigh participate in research at the Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason (BRI), where researchers are revolutionizing our understanding of T1D and setting the stage for game-changing treatments.

“We’re proud to be a world-leader in type 1 diabetes research,” says BRI President Jane Buckner, MD, “and working to transform care for millions of people by pursuing everything from therapies that prevent the disease to treatments for people who’ve had it for decades.”

A Holy Grail

In T1D, immune cells attack the pancreas until they destroy its ability to produce insulin—a key hormone that regulates blood sugar. As a result, people with T1D require insulin injections. BRI researchers have spent more than two decades pursuing one of T1D research’s holy grails: a way to halt the disease before insulin production stops.

As a critical first step, investigators from Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet—a worldwide network of top T1D researchers including many based at BRI—conducted a study that screened more than 200,000 people with a family history of the disease. The researchers kept track of which patients developed T1D and painstakingly analyzed blood samples from each person, looking for markers that could help predict who gets the disease.

This led to a groundbreaking discovery: Patients who have two or more key autoantibodies (markers in the blood that tell researchers the body is attacking insulin-producing cells) are considered in stage one of T1D and the vast majority of them will go on to be clinically diagnosed with the disease. Scientists often compare using autoantibodies to predict T1D, to using high blood pressure to predict heart disease.

“Now we can match people in stage one with clinical trials of therapies that try to prevent the disease or slow it down,” says Dr. Carla Greenbaum, MD, who heads BRI’s Diabetes Clinical Research Program and is TrialNet’s chair.

Slowing Immune Attacks

The Diabetes Clinical Research Program is the overarching umbrella of BRI’s T1D research. It encompasses many BRI researchers and staff members, and is integrally connected with TrialNet and other key research initiatives.

Under Dr. Greenbaum’s direction, BRI and TrialNet are leading clinical trials that explore ways to stop T1D. The TrialNet trials take place worldwide, and are supported by the TrialNet Clinical Network Hub, which is housed at BRI. BRI is also one of 24 TrialNet sites that offer clinical trials to patients and collect data.

These trials have the potential to transform the lives of people like Kayleigh, who tested positive for multiple T1D autoantibodies. She’s participating in a TrialNet study to see if an innovative drug called abatacept can slow immune attacks and extend T1D patients’ ability to produce insulin.

“We know that producing even a little insulin can dampen T1D’s effects and help people stay healthier,” Dr. Greenbaum says, “so the longer a patient can do that, the better.”

When Kayleigh joined the study in 2017, she and Merry had to make regular 90-minute treks from their home in Port Orchard to BRI’s Clinical Research Center. Each time, Kayleigh spent two hours in a hospital bed while the drug or a placebo—she won’t know which until the study’s over—was infused into her blood. Then she and her mom enjoyed exploring Seattle before taking the ferry home.

“I’d love it if we find out I’ve been taking the drug and that it will help me stay healthier,” Kayleigh says. “But even if the study doesn’t help me, I like knowing that it gives researchers information that could eventually help other people.”

Kickstarting Insulin Production

For years, researchers thought it was impossible to restore the body’s ability to produce insulin. The reason? They thought that T1D completely destroyed the beta cells that produce insulin. BRI scientists helped change that assumption by showing that many people with longstanding T1D have “sleeping beta cells” that make a hormone called pro-insulin.

Normally, beta cells chop up pro-insulin to turn it into usable insulin. But sleeping beta cells have lost their molecular scissors.

Dr. Greenbaum is leading the first study of a drug that could kickstart these sleeping cells so they make full-fledged insulin. Merry was among the first patients in this study, which is only available at BRI and at the Rocky Mountain Diabetes and Osteoporosis Center in Idaho.

“I thought my chance at being part of research on a new therapy was dead and gone,” Merry says. “It’s incredibly exciting to know that BRI is creating hope even for people like me, after decades of living with this disease.”

Hope for the Future

Today, Kayleigh is a high school sophomore who’s hatching plans to become a neonatal intensive care nurse.

“My experience with type 1 and BRI showed me how science and medicine can improve people’s lives, and helped me want to be part of something that’s larger than myself,” she says.

This sense of perspective might seem out of place in a 15-year-old—until you hear her mom talk about the family’s commitment to research.

“We might always live with type 1, but it will be a huge success if we can help researchers prevent it in other people,” Merry says. “This disease goes back five generations in my family and BRI gives me hope that even if my kids get it, my grandchildren won’t.”

Immuno-what? Hear the latest from BRI

Keep up to date on our latest research, new clinical trials and exciting publications.