In reality, there were just too many variables. For our plan to work in the field, we’d have to know how far Peter was going to walk, how much he was going to eat, how hot he was going to get, and how much insulin was in his body - and ask a college student with no training in managing a complex chronic disease to be our eyes, ears, and hands on the ground.

I don’t think we made it past day two.

In the moment, the failed experiment stung. And why wouldn’t it? As parents, we’re all conditioned to be believe that if our kids can dream it, they can do it. When Peter was diagnosed, the medical team made sure to stress that Peter could still grow up to be anything he wanted to be, except a fighter pilot.

(Joke’s on you, type 1 diabetes, Peter hates flying!)

The doctors even listed examples of high-achievers living with type 1 diabetes, including professional athletes, actors, musicians, and one Supreme Court Justice. That’s all good. We do want Peter to live in a world where people with type 1 diabetes are sticking it to the disease in every way imaginable.

The trick is making sure these exceptional stories give meaning to our lives down here on earth. To put it another way, reading that a modern-day explorer with type 1 diabetes has reached the North Pole is inspiring, but how am I supposed to feel when my family can’t manage a safe, practical solution for Peter to participate in nature camp?

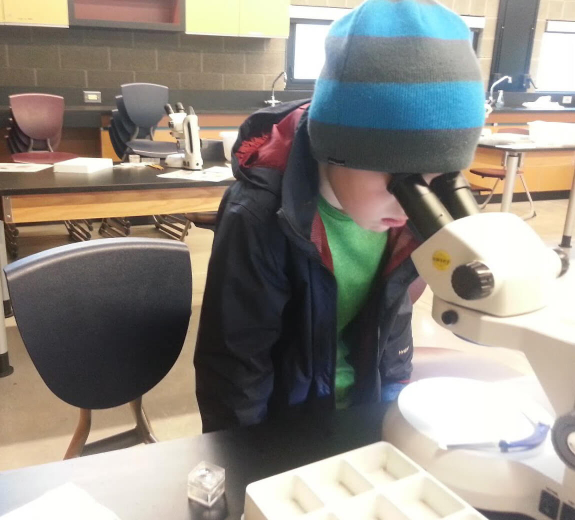

Maybe the answer can be found back in the lab. How does the team at BRI react when they realize a clinical trial doesn’t prevent or delay onset of type 1 diabetes? They learn, adapt, and move forward.

That’s how a family living with type 1 diabetes rolls. When blood sugar spikes after a slice of cake, we don’t stop going to birthday parties. We adjust the timing and dosage of insulin. And when a low blood sugar complicates nature camps, we don’t give up on camps. We adapt and move forward.

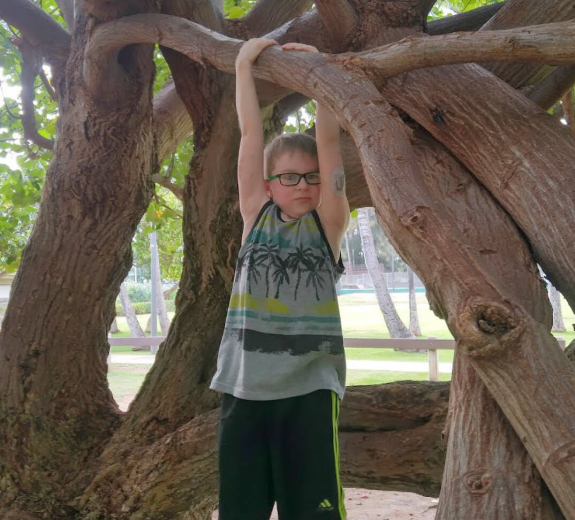

This summer, we’ll do our nature exploration as a family, and Peter will be in camps that open him up to new worlds, only without quite so many variables. In one typical week, he’ll spend five afternoons exploring his inner artist in Pottery camp while I work from a quiet corner - out of sight, out of mind, but not out of range.

It’s a new experiment. It won’t go perfectly. All I know for sure is that we’ll learn from it.

In the field, life with type 1 diabetes is messy, more art than science. We can perform the same action on two different days and get completely different results. The unpredictability itself is a lesson in patience. But, like research in the lab, the experiment must go on. That’s how we roll.