Scientists have only begun to scratch the surface of the science behind food allergies. And as they continue to piece together global data, we may find that allergies are more interconnected than we think. While this bigger picture begins to take shape, we can all take part by sharing stories, information, and lessons to ensure a safer and better future for those of us who are affected.

Food Allergies Around the World: What We Know, and What We Don’t

If you’re one of the 220 to 520 million people around the world living with a food allergy, odds are you have to think about it every day. Maybe you’ve declined a dinner invitation to avoid your culprit food, or found yourself deciphering vague product labels in the grocery store aisle – or maybe you live in part of the world where there are no laws requiring manufacturers to label food ingredients at all, and you’re left guessing.

If you do make contact with an allergen, what then? In many cases, food allergies are the most dangerous – even life-threatening – form of allergy. In the US alone, food allergies are responsible for about 30,000 anaphylactic episodes per year resulting in 2,000 hospitalizations and 200 deaths. And severe reactions aren’t always triggered from ingestion, but also from skin contact or inhalation. That can make your allergen incredibly hard to avoid.

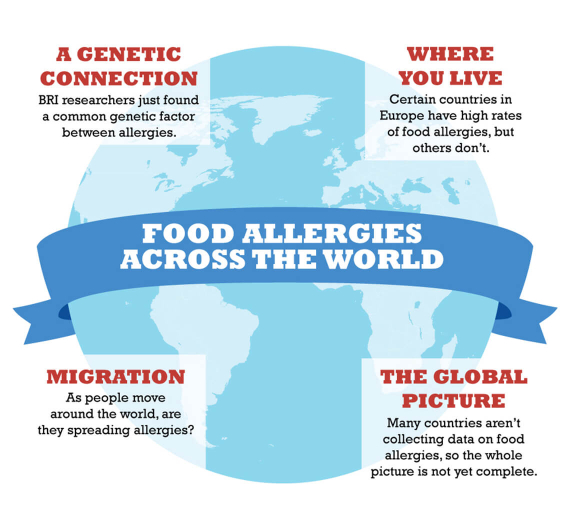

If you’re up against the threat of food allergies every day, you may be in search of more information about where they come from and what we can do about them. The reality is that right now, the global community is only just beginning to understand them. But, researchers around the world (including teams right here at BRI) are beginning to make real progress.

Here are some things we do know |

However, along with progress come more questions and challenges |

|

A cellular culprit: Recent research from BRI uncovered a type of cell believed to drive all allergies, which means they may be more connected than we think. This breakthrough is a big deal for people with all types of allergies, and will help support research on better methods for diagnosis and treatment worldwide. |

How you get them: Scientists haven’t come to a consensus on the extent to which allergies are caused by environmental or genetic factors. In particular, we don’t yet understand the role of environmental factors in triggering allergic reactions, especially to food. And we’re not sure what your sister’s allergy to peanuts might mean for you. |

|

Where you live: Data from a 2010 study revealed varying degrees of food allergies between a group of Western countries, with the US, Germany, Italy, and Norway having the highest sensitivity and Iceland, Spain, France, and the UK with the lowest. However, these allergies weren’t clearly linked to different diets, so the connections remain a mystery. |

The complete picture: Many countries aren’t collecting data just yet. This means that for many people around the world, information on allergies isn’t that easy to find, and certainly not in one central place. It also means that our global estimates are based on limited research samples, which may not paint a complete picture. |

|

Uncommon Knowledge: The same study also discovered that certain food allergies, such as milk and eggs, were less common than patterns of sensitivity to foods like hazelnuts, shrimp, wheat and apples. Makes you wonder what other misconceptions there are to dispel! |

People on the move: As the world becomes more interconnected, scientists are also starting to debate the role that migration and globalization plays in spreading allergies. This will difficult to track, but important to keep in mind as new discoveries are made. |

|

Rethinking treatment: Immunotherapy treatments (allergens given as a shot or placed under your tongue) have traditionally been used for people with allergies, and are recently being used for people with food allergies too. Based on research from the Immune Tolerance Network, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases just came out with new clinical guidelines suggesting things like giving infants peanut-containing foods to limit their risk for developing an allergy. |

What’s at stake: In addition to being life-threating, food allergies can have a negative socio-economic impact in many parts of the world. For instance, children – who are at a higher risk than adults for developing a food allergy – may have trouble staying at school all if they can’t eat the lunch. Then their mothers or fathers have to leave work to take care of them. That means they’re all missing out on opportunities to learn or work, creating an economic loss for their community. |

Immuno-what? Hear the latest from BRI

Keep up to date on our latest research, new clinical trials and exciting publications.